So you're here to autopsy a deadout...

Wait! Are you sure that hive is dead?

Bring your veil, and wear it until you confirm there isn't a small cluster tucked into the hive.

Sometimes on a warm day (and 50 sure seems warm sometimes!) after a long cold stretch, the honey in the hive has not

yet warmed up, keeping the temps IN the hive cold still. The cluster may be fine,

just waiting for a warmer day.

Or maybe the bees just prefer to stay in when there isn't forage. Something like 20% of my hives are like that.

That way, they conserve foragers who might otherwise have died in a weather-related accident. Landing on water

when it's only 50 out is no joke when you're that tiny!

I also sometimes use a stethoscope on the wood walls or top entrance to listen for bees,

and you can try that first if it's one of the first warmer days. Or anytime, really.

I do have to quarter each side of the box pretty thoroughly because if they are in the center, the cluster sound

is faint. It sounds like a crowded subway station from a distance.

Once you're sure they are dead, 2 simple steps are critical for your future success.

Take advantage of the opportunity to confirm or deny the role of Varroa in the hive's death. Once you learn to understand and identify a mite kill, you can prevent it from happening again. It's a bit more subtle than you might first expect....

1. Scoop up 1/2 cup of dead bees, and do a rinse on them.

You can use an alcohol wash vessel for this,

or use 2 plastic cups and mesh that keeps the bees in but lets out things that are 1 mm or so across.

If you count more than 30 mites in 1/2 cups of bees (that's 300), then the hive died of mites.

But where did those mites come from? Were they

imported when your (clean) hive went robbing in the fall, or home-grown? To decide that, do step 2...

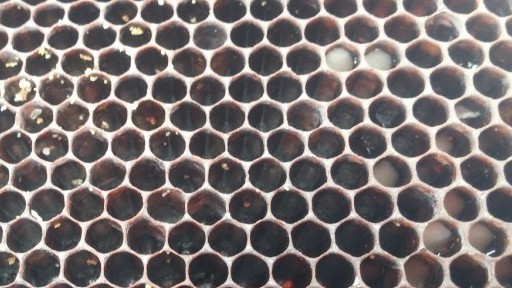

2. Check the ROOF of the central brood comb for mite frass.

Mite frass is mite poop. The above comb (pic courtesy of

Bee Informed

Partnership) is tipped so we can see into the roof of the cells. The tiny white

dots are mite frass, deposited when the mite successfully reproduces. The solid white

patches are crystallized honey that re-liquified.

If you see many mites in the

alcohol wash of dead bees, then mites played a role in killing the hive. If you see

this much mite frass, then the mites were home-grown over the summer.

But... you could see lots of mites in the alcohol wash with NO mite frass.

The lack of mite frass means few mites were reproducing during the summer, in your now-dead hive. That's good. Keep doing what you did

to keep mites low through September.

The presence of mites despite the lack of mite frass means the hive went out and robbed after you treated.

That information changes WHEN you would treat. You will need late September through mid November mite treatments.

A hive autopsy - hard to find the silver lining...

Losing a hive hits one hard, even harder when you have few hives.

A deadout means we thought we were doing it right - we knew what was going on...

but we were wrong.

They did not die in vain...

I look at a deadout as a chance to never have that happen again. It's also a hive that generated a wealth - drawn comb. Be sure to protect it with the following steps:

- Remove dead bees from the bottom, and the frames as far as is possible. Rotting bees are gross.

- Close up the entrance well against other bees and mice. No sense in losing any remaining honey from robbers, when you could dispense it to those in need.

- Either freeze it, or be sure the outdoor temps went lower than 10 degrees. Mother nature's freezer can kill small hive beetle eggs and wax moth eggs.

But don't bees die of things other than mites?

- In short, yes. There are 3 other main ways a hive can die:

- Starvation during winter.

- Late summer swarming reducing numbers and resulting in no queen for the fall/winter.

What does death by starvation look like?

If the hive has a cluster of bees, but no honey nearby, no honey above, then it starved. This is a much bigger risk for a small cluster. This can happen if a beekeeper takes the winter honey in the fall - not realizing that by taking the honey super off in September, the bees did not get any more nectar, and lost their honey to the beekeeper. When taking honey supers off that harvested late summer or fall honey, you MUST look for honey in the top frames 2 weeks later, signaling a nectar flow. Otherwise plan to feed for 2 weeks straight, 2 gallons a week. 1 gallon fills 2 frames, so 4 gallons fills more than half of a deep.

What does death by fall swarming or failed supercedure look like?

In Ohio, a hive may get a fall nectar flow that triggers the hive to swarm. Stupid bees. Then, the hive can go from

15 frames covered with bees to 7. Most of the bees on the comb in early Sept

are summer bees, and will die in 2 weeks. Come early Oct, the only bees left alive (mostly) are those born in September.

So for this example, the hive went from 14 to 7 due to swarming, and will go to 3.5 due to natural death of summer bees.

To top off this obstacle, the hive will not have as many "winter bees" born. If the queen comes back mated,

in late Sept, she may lay for 4 weeks. Then it's too cold and there's no pollen anyways. She may only lay enough winter bees

to get the hive to 4 frames covered with bees. That's not enough to get through winter, in Ohio.

The signs of this death are a strong hive in August, half the size in September, previously good

solid capped brood, low mites, low mite frass, possibly an opened queen cell - and a couple frames with dead bees in December.

Things that did not kill your hive...despite many claims it is possible

I don't credit a couple of popular causes of death that I've seen floating around. These include:

- the cold,

- yellowjackets,

- absconding, and

- poor ventilation or high moisture.

A hive that is dwindling will be at risk for many other ills, but really died due to

whatever led them to dwindle in numbers.

A hive with too few bees cannot properly regulate its inner environment, which is critical for bees.

They are living beings, a superorganism the size of a small dog. This regulation includes cooling the

hive when it is hot, and fanning to spread air when ripening honey, and gentle movements while the

hive is clustered in the winter that permit air movement and bees carrying warmth and food through the

cluster.

A hive with too few bees cannot defend itself from robbing attemps by their sisters or neighbor bees,

or from yellow jackets, or wax moth or small hive beetle. Again, the actual cause of death is

whatever led their numbers to dwindle in the first place.